Grandmaster Chess Therapy

How to get beyond winning and losing while still winning more than losing 🙃

In a world that can seem shallow, chess meets a longing for depth. In a world that can feel lonely and confusing, chess offers the experience of shared meaning and mattering. In a world of shrill whataboutery that pretends to be debate, chess offers rule-bound intellectual clarity. In a distracted world, chess reminds us of the peace and joy of concentration. In a life where we are rarely quite sure who we are, chess offers us the responsibility towards the next move, which is ours alone to decide; for moment after tremulous moment, that decision-maker with our life on the line is who we are. And in a world where we often feel stuck, chess offers self-overcoming, that delicious realisation when you notice you’re no longer making the same mistakes.

You may have heard of the chess boom - a rapid increase in people playing chess. We can trace the causes to the pandemic, The Queen’s Gambit on Netflix, Magnus Carlsen’s charisma, the rise of social media streaming, or even smartphone addiction. All of these historical, technological and cultural factors are important, and the chess boom is a story of simple fun, distraction, and entertainment. But that’s not the whole story. At the heart of the boom is the heart of the game, which is the human being, our experience of figuring things out, and how chess speaks to perennial human needs and desires relating to identity and meaning. Some people think there is only story in chess - the story of victory and defeat - but in my experience that story is merely the setting for all sorts of other stories to play out.1

I have watched the chess boom unfold from a rare vantage point of being somebody formed by the game - I started playing when I was five and I am a Grandmaster and three-time British Chess Champion - but then left chess behind in my early thirties to pursue a different life, only to look at the chess world as if as an outsider, and wonder what I am missing out on. Some spiritual traditions speak of the human recognition that we may be more than merely human, that we are not entirely of this earth, in terms of the expression ‘in this world but not of it’. For me, with chess, it’s the other way round. With chess, I am of the world but not in it.

That’s ok with me, and it’s not likely to change. At forty-eight, life is full, my passion now lies in a different kind of work, and my responsibility is less to my knights and bishops and more to my young family and the communities I am part of. I can still show up for a few hours to play or teach chess or even write about it, and I sometimes do. However, it does not feel like my main arena any more, and I can no longer justify giving oodles of time to prepare openings, or to re-enter the chess world with any clarity of purpose other than pleasure or nostalgia. Yet I definitely feel more fully myself when chess is a small part of my life, and given how many people helped me along the way, it feels like my duty to share some of the expertise I have acquired. The challenge has been to figure out how to contribute from a vantage point that is distinct, meaningful and practical.

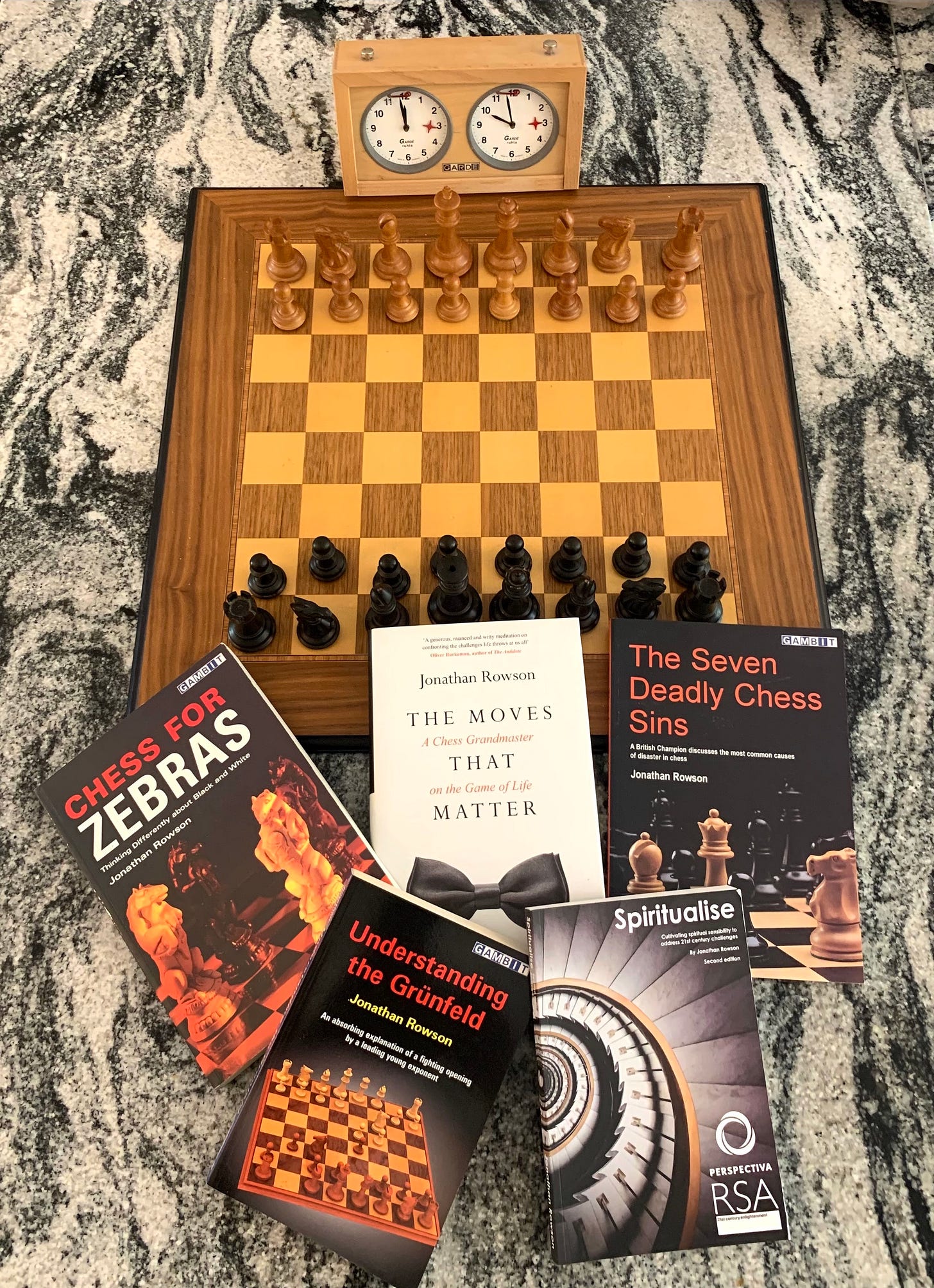

I’ve noticed that my approach to chess has become increasingly philosophical and psychological, and I even see the game as a kind of spiritual practice (and perhaps this informed my later publication, Spiritualise). Please be assured that I still like to win! It’s just that I see winning from a broader perspective now. Any competitive endeavour calls for the suspension of disbelief about what you profess to care about, whether it’s chasing a ball for ninety minutes, shooting hoops, or improving your endgame technique. I love a good tactic as much as the next player, the drama of the contest is familiar to me, the joy of victory and the pain of defeat; but chess was always about more than chess for me, and I wrote about that at length in my chess memoir, The Moves that Matter (Bloomsbury 2019).

While teaching children, I keep chess relatively simple. I encourage reflection on how we think, but the focus is on knowledge, patterns, fun, ethos, learning, and excitement.

Adult students will testify that my lessons with them are a bit different. Thoreau famously said that many people go fishing all their lives without realising that it’s not fish they are after, and I feel the same way about chess. What do these people - husbands, accountants, grandfathers, lawyers, IT professionals, students, teachers - hunched over, faces creased with tension, stationary for hours, craving some positional objective and dreading a tactical oversight - what do such people think they are doing?

In adulthood I think chesss improvement is possible, but it’s a different kin of challenge because it’s as much about unlearning through self-awareness as it is about learning through study, practice, and acquisition. I wrote about this in Chess for Zebras(2005) especially, but also to some extent in The Seven Deadly Chess Sins(2001). Both books are still selling remarkably well almost two decades later and I think that’s because I dared to be honest about just how emotional and psychological this purportedly logical game can be. In essence, adults have to unlearn because they see with what they already know to a greater extent, their motivations are more complex, their decisions are often tied up with an identity structure about how chess allows them to experience who they are, or at least who they want to be. So when teaching adults, especially those over twenty-five or so, I tend to mix variations, knowledge and insight about the game with a form of something resembling life coaching. I ask players to talk me through their thoughts and feelings about their moves, and the position on the board speaks to the many meanings of life. Yet I keep coming back to the objective truth of the position too - chess is valuable precisely because there often is a fact of the matter; it’s not all relative. It’s not all a matter of opinion. If you’re in check, you have to get out of check. And checkmate ends the game.

Chess can be defined in many ways, but it is a microcosm of life in which we are the co-author of a story that always starts all over again and plays out differently every time, each game is a day-in-the-life of the person playing. The game is also a mirror, in which we can see our psyches in all their wounded and wilful complexity. I have written about all of these things in my books and essays, but engaging with such material is not like learnign facts. It’s more like a form of practice, or participatory knowing in which chess is our vessel of self-discovery, our opponent is the resistance we need, and it helps to have someone experienced there to listen, and talk it all over.

At a time when chess is becoming ever more technological and algorithmic, I have decided I would like to explore a deeper story, not yet properly told, about chess as a kind of therapy. Chess therapy is not psychotherapy, and I am not ‘a therapist’ as such, but for what it’s worth, I took a master’s course on psychotherapy in which we learned about the theory behind the various schools of practice while simulating a therapeutic process, and I did undergo a form of psychosynthesis psychotherapy for over a year in my mid-thirties.

“We may define therapy as a search for value”, said Abraham Maslow, and that means many things. There is the value of winning, of course, which could be framed as the pursuit of excellent, but there is also the value of knowing your mind and emotions and motivations better, of understanding yourself as a learner and a competitor, and by extension, beginning to understand others, and the nature of human existence too. I believe people play chess because they are looking for something, and that something is often themselves. Chess therapy begins with chess, but it doesn’t end there. If Chess is a kind of escapism, chess therapy is about helping us understand what we are trying to escape from and to.

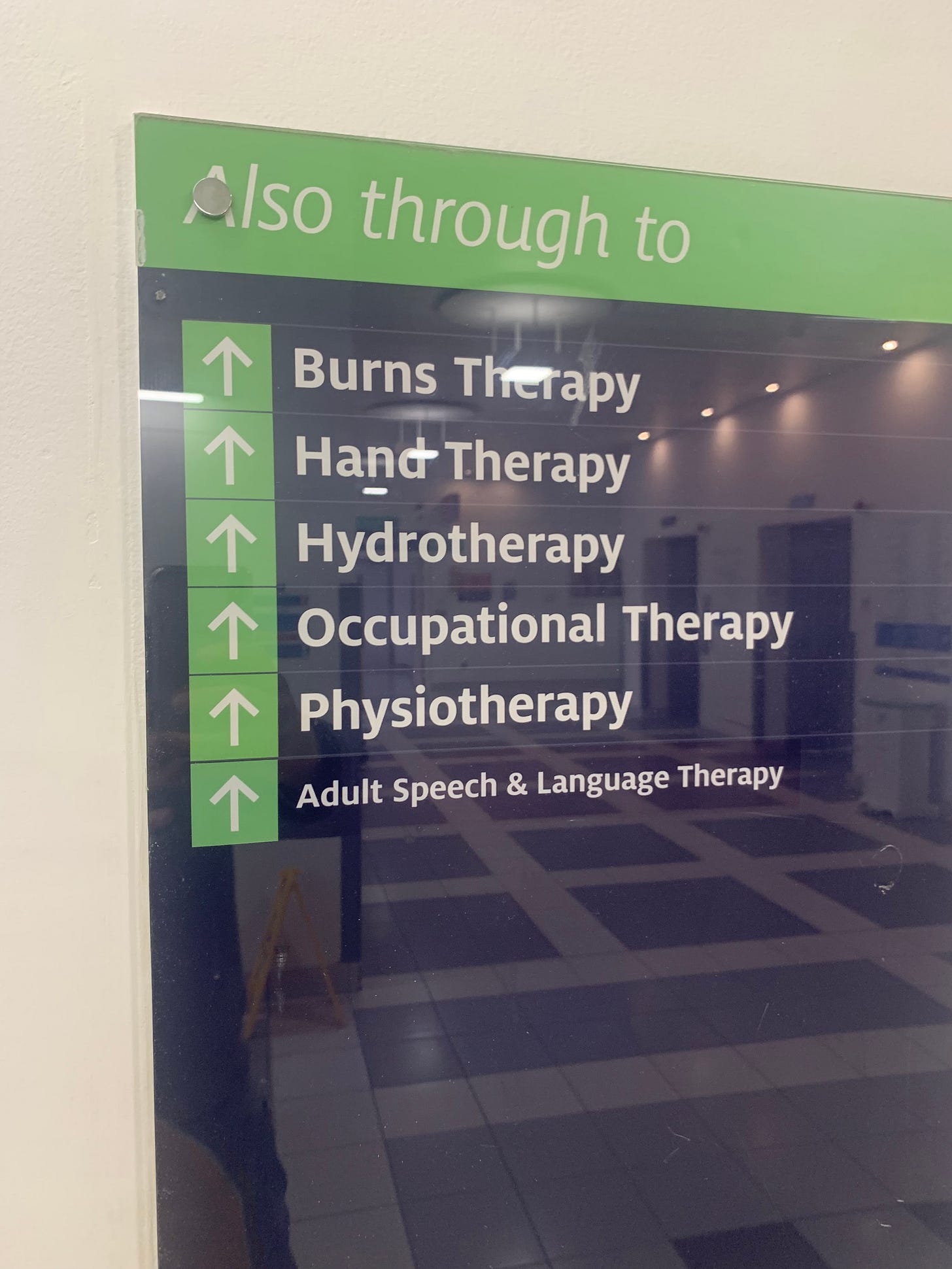

Everyone is in some kind of therapy, but we are not always aware of it. Most people have heard of aromatherapy - the therapy of smell; hydrotherapy – the therapy of water; physiotherapy – the body taking care of itself; and hypnotherapy – accessing deeper levels of the psyche. But there is also retail therapy, book therapy, pub therapy, and so on. A few weeks ago, I was in Chelsea and Westminster Hospital and smiled at this sign:

I started to wonder which other therapy services might be on offer. I remembered existential therapy, cosmic insignificance therapy, and then the whole gamut of psychotherapies. In general, therapy is about attending to some feature of life with care, in a way that helps you care for yourself.

In that context, what might ‘chess therapy’ mean?

***

I expect my thinking will evolve here based on practice, but at first blush, I see four main purposes of chess therapy, all of which can lead to better results, but none of which are directly designed to do so.

Rebalancing extrinsic and intrinsic motivation.

How might getting winning in perspective both help you to win, and to care less about winning? How does understanding your reasons for playing chess help you put more into it, and get more out of it?

Developing metacognition

A deeper grasp of how chess thinking processes lead us astray. Knowing your mind better. The dark side of pattern recognition, cognitive biases, hidden assumptions, unhelpful memories, and storytelling.

Acknowledging emotional needs

Understanding how chess’s role in meeting emotional needs affects decisions over the board: ego, status, belonging, competence, desire…

Holding your chess identity lightly.

Chess’s role in establishing, maintaining, negotiating and transcending identity.

Why do you play the openings you do? Which myth are you playing by? Why do some mistakes matter to you more than others?

All four of these initial themes are explored by analysing one’s games more carefully than most people do, and the main material of chess therapy is the interactive discussion and analysis about the games themselves. I foresee the following modalities:

One-to-one in person chess therapy, where we analyse games and talk over what they mean for the player as a competitor, and in the context of life as a whole.

In person group therapy, where each player allows the others watching to share in the chess therapy, and either learns by osmosis, or asks their own questions of the position in a way that is of benefit to them.

Digital chess therapy - this can be in either an individual or group form. It occurs to me that the ideal group will be players of a similar ability who know each other, but some variation in ability can also be helpful, particularly for the relatively weak players.

**

The Second Mountain

In principle, chess therapy is for anyone of any age, but it is best suited to players in midlife who are wondering why they keep playing, what they are playing for, and why they keep making the same mistakes.

One way to understand chess therapy is that it is mostly a practice to help inform the task of climbing ‘the second mountain’. This term has a history, but it came to prominence through the book by New York Times columnist, David Brooks, called The Second Mountain. The idea is that the first mountain of life is about achievement and identity through making your way in the world, in which, as the storyteller Martin Shaw puts it, we “earn our name”. But at some point, that story runs out, and then the challenge is to commit to something other than ourselves; which means that chess then becomes a kind of practice that fortifies and consoles us as we make our way in the life we live outside the game. I’d like to share what that means to me, but I trust we all have some version of this phenomenon.

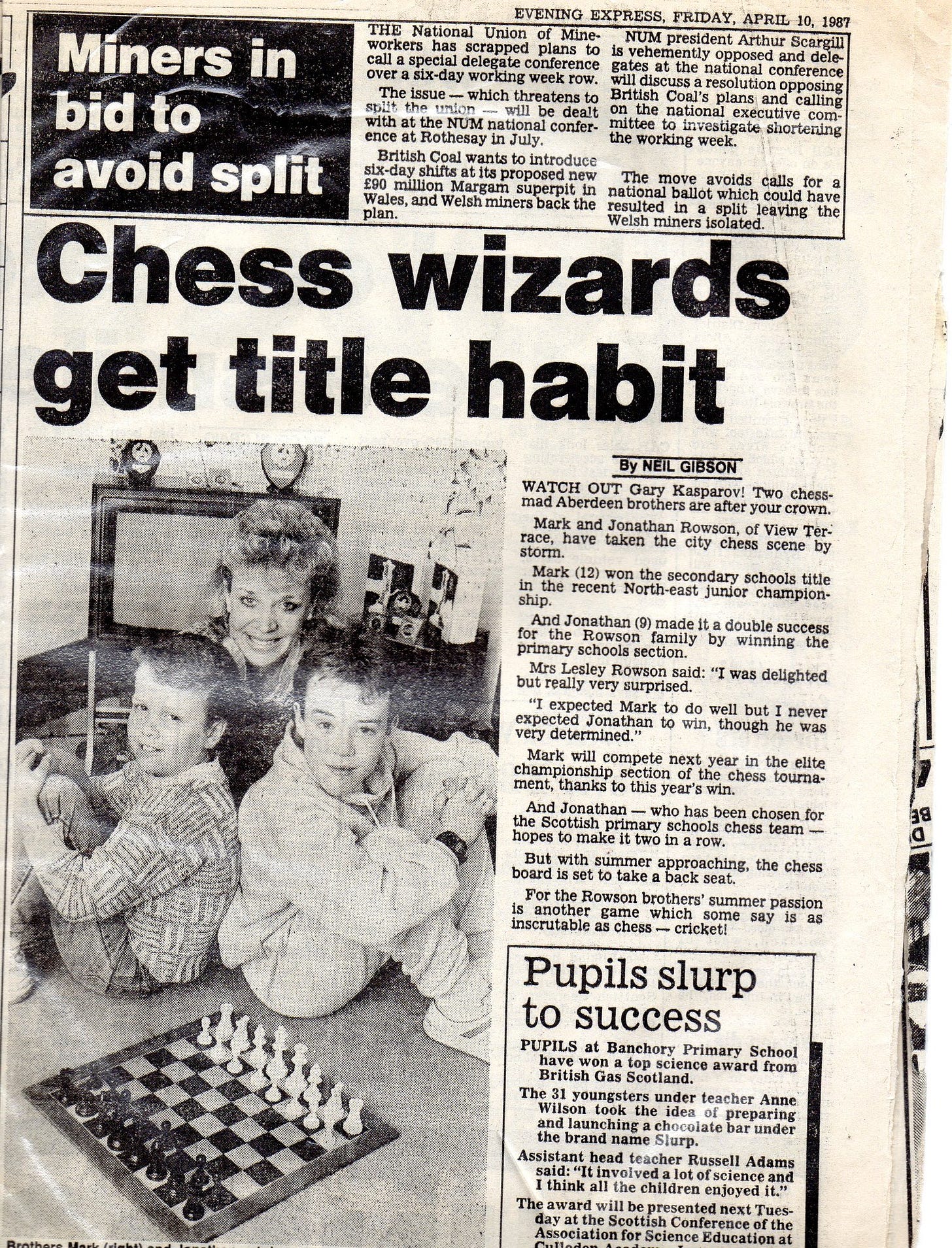

I was born in Aberdeen in 1977 during the Cold War, when Anatoly Karpov was world chess champion. I learned the moves when I was five years old, played casually at home with my brother Mark and at primary and secondary school. I started to ‘get good’ around the age of ten when family life became complicated and the game became a kind of escape.

I became a Chess Grandmaster in 1999, I was a three-time British Chess Champion between 2004 and 2006, and I am probably Scotland’s strongest ever player (at least for now). My highest published FIDE rating was 2599, which I achieved three times just to wind everyone up, including myself (for the record, I did achieve my target of 2600 between lists). I have competed with Magnus Carlsen and other World Champions and elite players, and I didn’t always lose. I have written three popular chess books that are all still being read: Understanding the Grunfeld (1999), The Seven Deadly Chess Sins (2001) and Chess for Zebras (2005).

In 2008, I was on the analytical team of Viswanathan Anand. My contribution was relatively small, mostly over one ten-day summer camp, where I helped him build his new 1.d4 repertoire for his successful match against Vladimir Kramnik. I was invited back to help again, but life moved on. I wrote fifty book review columns for New in Chess magazine, analysed numerous opening variations for Informator, Chess Publishing and ChessBase. I share all this to say that I have done my time climbing the first mountain. Whatever chess is for me now, it’s not about achievement.

I also spent eight years in higher education studying Philosophy, Politics and Economics at Oxford University; Mind, Brain and Education at Harvard University and a PhD on the concept of Wisdom at Bristol University. Since 2009, I have been working as an intellectual and social entrepreneur in public policy research and social innovation. My day job is that I am co-founder and Chess Executive of Perspectiva, which is a registered charity, book publisher, project incubator, research institute and practice innovation hub.

So where does chess fit in to that? It fits in as a way to keep myself together. I see chess as a reliable reference point; at once a map, compass and walking stick as I try to make my way up the second mountain.

I have known for a while now that I am a chess therapist, but I am still figuring out what it means and how to make time for it. I’ve been thinking about this question for over a year now. I was in discussions with a major chess platform about bringing chess therapy to the masses, but I did not feel ready, and couldn’t mobilise the attention required to make it happen. I thought it was just because I was busy, but then I realised the problem was that I had to take it more slowly. I had not yet properly done my own chess therapy, and needed to do that before offering it to others. I think I am ready now, but let’s see.

I don’t yet know how it’s going to work, but I am starting with a few talks about chess therapy in London, starting on Monday May 5th, and I will be doing a few drop-in chess therapy sessions at The Mind Sports Centre in Hammersmith, London on Mondays thereafter, from roughly 6-7. The best raw material of chess therapy is always recent games, but I do have material of my own to elicit a therapeutic process when no such games are available. If there is sufficient demand, I will do some group sessions online, perhaps monthly. I will also use this platform to write about chess whenever the desire arises.

I am a Grandmaster, and I am doing this work after hours, so in future there may well be a pay wall to access what I get up to here. I plan to focus on quality rather than quantity, so I cannot promise weekly posts, but there will be regular material, including game analysis and perhaps some videos. I am not seeking a large audience, but the number of paid subscriptions will signal how much time I should set aside for this work - so if you would like to encourage me, please go ahead. The aim is more about finding a small group of people who get what I mean by chess therapy and want to do the work.

So if that’s you, please sign up!

Yours Aye,

Jonathan.

The sudden growth in people playing and watching chess started in the pandemic, when the ease of accessing an absorbing game online was a relief for many, and new chess technology platforms made chess players realise they are by no means alone. Social media has made online chess an enjoyable community experience, and chess streaming has proven to be a popular form of entertainment. The Queen’s Gambit Netflix series was a game-changer too, with many millions seduced by the game’s charms at a time when they had time to follow up by playing it (I loved the series too and shared my views on it here). And all of these factors were augmented by the presence of a charismatic and media-savvy world champion, Magnus Carlsen, who was so cool he didn’t feel the need to defend his title. And attention did not just go to the Elite. Chess streaming became entertainment. The legacy media seemed eager to follow heroic stories of chess’s role in African development, the Indian Chess boom, and so on. It is not easy to measure precisely how big the boom is, but it is measurable in principle in terms of online analytics and memberships of national chess federations. My old friend Peter Doggers recently wrote a book about this “Chess Revolution” which I have not read, but I believe goes into these details of the chess boom in more depth than I can here.

"co-founder and Chess Executive of Perspectiva"? Or co-founder and Chief Executive of Perspectiva"?